Anglican Edmund Calamy: Trembling for the Ark of God

Feb 26, 2016

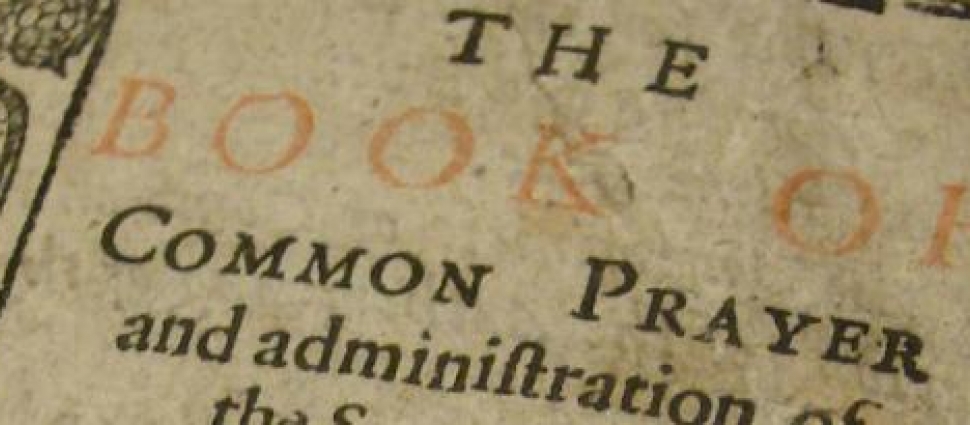

Last time I encouraged you (especially my fellow Anglicans!) to join me in reading the Puritan Paperback, Sermons of the Great Ejection. This title is a collection of nine sermons recalls one of the great turning points in English Christianity—when approximately two thousand ministers were deposed from the established Church in what was called “The Great Ejection.” These men were unable for the sake of their conscience to conform to a series of Restoration Parliament laws of The Clarendon Code.

Last time I encouraged you (especially my fellow Anglicans!) to join me in reading the Puritan Paperback, Sermons of the Great Ejection. This title is a collection of nine sermons recalls one of the great turning points in English Christianity—when approximately two thousand ministers were deposed from the established Church in what was called “The Great Ejection.” These men were unable for the sake of their conscience to conform to a series of Restoration Parliament laws of The Clarendon Code. The first sermon in this collection is one preached by Edmund Calamy on December 28, 1662, three months after the new laws took affect. Calamy rejected the doctrine of church government known as episcopacy as he believed a heirarchy of superior ministerial offices lacked biblical foundation. Because of his understanding of the equality of bishops with presbyters, he was a member of the network of like-minded men who were labelled “presbyterian” and was a member of the Westminster Assembly.

As a testimony to Calamy’s integrity, he was one of a number of Church of England clergy that opposed the execution of King Charles I and was one of the ones who took the initiative to invite his son, Charles II, to return to England after the death of Oliver Cromwell. He turned down several bishoprics and had hoped of a settlement and attended the Savoy Conference in 1661. His hopes were dashed at the result and he was duly ejected the following year. He continued to attend his old parish church of St. Mary’s Aldermansbury in London where he ministered as parish priest for 23 years. The church was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. Devestated at its loss, elderly and in frail health, he died soon after and was buried in the ruins of the church near where the pulpit stood.

Calamy was already deposed and sitting as a member of the congregation when he was asked to preach because the scheduled minister did not arrive. Preaching unprepared from 1 Samuel 4:13, he was later arrested for preaching, then ordered released by the King after a riot broke out when word of his jailing spread.

The sermon follows the pattern of the majority of Puritan sermons of the period. The text is analysed so that the plain and simple meaning is clear to the congregation. The biblical doctrines that are either clearly stated in the text of may be deduced from the text are then explained. The sermon concludes with a series of “usuages” or what we would understand as the application of the scriptural principles to the congregation.

What is impressive in Calamy’s exegesis and doctrinal analysis is the depth of his understanding of God’s providence. He sees the work of God in a nuanced way that brings judgment upon unbelief and sanctifying trial to believers who have trusted in Christ. They cannot be separated. Calamy speaks to us today in his call to us from God’s Word that we must strive to holiness in the face national trouble.

He is concerned that they do not abandon their gathering together under God’s ministry, nor try to usurp the proper place of preaching through the Lord's called ministers. He calls the congregation to a more faithful trust in what God is doing in their lives by exhorting them to not look to the politics of their time or to lament the failure of their duty to the gospel in past generations, but to study in God’s Word and to devote more time to prayer and holiness of life so that they may trust our heavenly Father ever more deeply in what were testing times.

This is the great temptation, isn’t it? It is the temptation to consider that our heavenly Father is not to be trusted.