Anglican John Collins: Contending for the Faith

Mar 25, 2016

We are at the third (see part 1 and part 2) of our reading the Puritan Paperback, Sermons of the Great Ejection. This title is a collection of nine sermons recalls one of the great turning points in English Christianity—when two thousand ministers were deposed from the established Church in what was called “The Great Ejection.” The were unable for the sake of their conscience to conform to a series of Restoration Parliament laws of the Clarendon Code. The third sermon in the collection is one preached by John Collins. Collins is interesting for a number of reasons.

We are at the third (see part 1 and part 2) of our reading the Puritan Paperback, Sermons of the Great Ejection. This title is a collection of nine sermons recalls one of the great turning points in English Christianity—when two thousand ministers were deposed from the established Church in what was called “The Great Ejection.” The were unable for the sake of their conscience to conform to a series of Restoration Parliament laws of the Clarendon Code. The third sermon in the collection is one preached by John Collins. Collins is interesting for a number of reasons. The first is his early years. Although born in England, he was raised in America, in New England, graduating from Harvard in 1649. He was a teaching fellow there for four years. He then returned to England serving as a military chaplain.

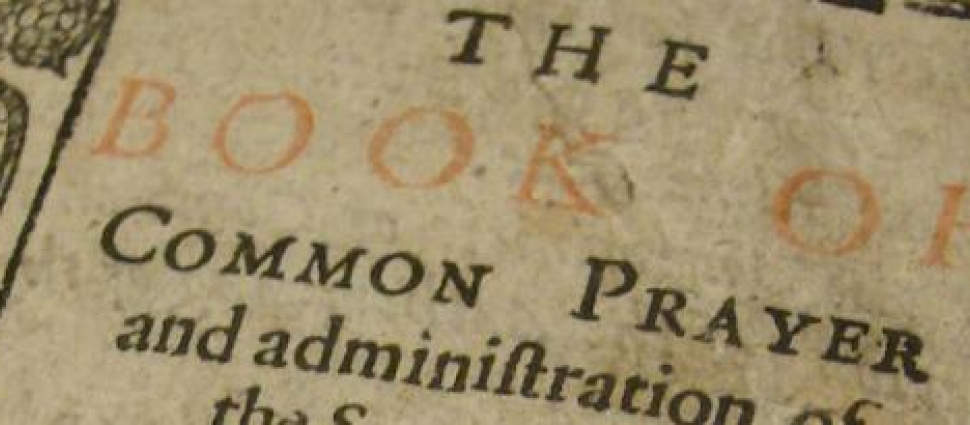

The second is his ministry. He was a “lecturer.” Lectureships we separately endowed parish teaching/preaching positions that enabled ministers to avoid the canonical restrictions on parish clergy. Lectures were additional services set aside at times other than the required Book of Common Prayer services. They were led by sympathetic Anglican Puritan ministers who were contracted by a “corporation,” a committee of laymen. What is fascinating about the lectureships is how they gave the laity an authority in doctrine and ministry that rivalled that of bishops and is evidence of their desire to hear sermons throughout the week. After the Ejection a number of London corporations established lectureships and halls for ejected ministers and their congregations that would open, serve a congregation for a time, be raided by Crown officers only to reopen in another location in the City.

The third is the context of the sermon itself. It was preached at Pinner’s Hall in 1672 (the Pinmaker’s Company was a corporation made up of pin manufacturers that appointed Collins as one of the lecturers there) when the ejected were able to worship freely without fear of arrest during a period of general amnesty for religious non-conformity. Charles II, a king sympathetic to Roman Catholicism that converted to Rome on his death-bed, used various acts of religious amnesty in his political manouvers against parliament to ease restrictions against Roman Catholics. Ejected ministers and their congregations had to endure being the political football between kings and parliaments from 1660-1689. Collins’ sermon gives us a glimpse of the believer’s life in the midst of the 26 years of persecution that followed the Great Ejection. I recommend for further reading Gerald Craig’s classic, Puritanism in the Period of the Great Persecution 1660-1688 for a detailed history of the times.

Collins’ sermon text is Jude 3b: “…earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints” and follows the pattern of exegesis of the text to biblical doctrine(s) in the text to application or usuages of the doctrine to the believer. It is clear throughout the sermon that the ten-year persecution of ejected ministers and their congregations has taken its toll. Fewer are remaining faithful to the gospel. It seems it is one thing to participate in a doctrinal disagreement with the majority that dismissed you as being foolish before the Great Ejection, it is quite another thing to be considered morally dangerous to the realm by that same majority afterwards. They will simply not allow you to go about your daily business unhindered as before. Many conformed. Collins gives four arguments that former believers used to rationalize their abandonment of the gospel:

- The list of essential biblical doctrines keeps changing. So many doctrines seem to be indifferent. Why would I risk so much when the position I now hold may be one that turns out to be non-essential?

- I am willing to give up much for my Savior, but there is a limit. When it comes to “collateral damage” the burden is too great. How can I allow others to be endangered by their association with me?

- News has come to me that another trusted church leader has changed his mind and now conforms. Many have come to faith in Christ under their ministries. I have read his sermons on other matters and they seem biblically sound to me. Why shouldn’t I follow him into conformity?

- It does no good to stand out. What point does my suffering prove? How is the gospel ministry to survive if we are all locked up in prison or worse?

How would you respond to these arguments today? What would your answers be?