Anglican Thomas Brooks: A Pastor’s Legacies

Mar 11, 2016

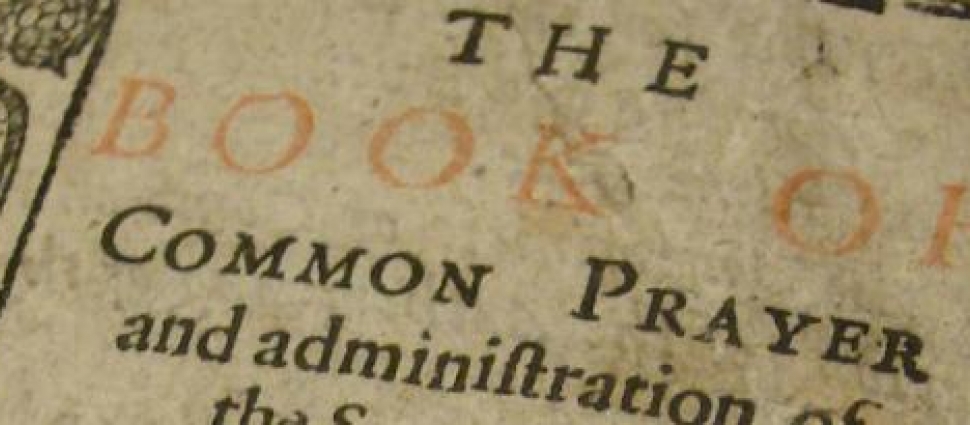

We are at the second of our reading the Puritan Paperback, Sermons of the Great Ejection. This title is a collection of nine sermons recalls one of the great turning points in English Christianity—when two thousand ministers were deposed from the established Church in what was called “The Great Ejection.” The were unable for the sake of their conscience to conform to a series of Restoration Parliament laws of the Clarendon Code.

We are at the second of our reading the Puritan Paperback, Sermons of the Great Ejection. This title is a collection of nine sermons recalls one of the great turning points in English Christianity—when two thousand ministers were deposed from the established Church in what was called “The Great Ejection.” The were unable for the sake of their conscience to conform to a series of Restoration Parliament laws of the Clarendon Code. The second sermon in the collection is one preached by Thomas Brooks. In sharp contrast to last time’s Edmund Calmy, little is known of Brooks’ life except what he mentions in his writings. Brooks was ordained in 1640 serving for some years as a chaplain in the English Navy. He was made the rector of St. Margaret’s New Fish Street Hill near old London Bridge in 1652, serving there until the Ejection. He continued to preach in London, for some reason not suffering persecution like his colleagues. He remained in London during the Great Plague to minister to his parish even as other conforming ministers fled the City. Sadly, his old parish church was the first destroyed in the Great Fire the following year. It is thought Wren deliberately omitted St. Margaret’s from his rebuild of the City churches so that Brook’s pastoral base would be purged. Of all the Anglican Puritan divines republished by the Victorians in the 1840-60’s, Brooks was the most popular. He communicates profound truths in a simple manner and can be easily read by young and old. If limited to the purchase of a few Anglican Puritan works, be sure to buy and read Brooks. Nothing is known of the external circumstances of his last sermon at St. Margaret’s except that Brooks and his parish knew that he would not be allowed to preach to them again. The sermon is organized in two parts.

Part 1

The first part answers the question of the day: Why would men be in such opposition to the plain, consciencious preaching of the gospel? Brooks sets out the biblical position concerning man’s rebellion and his hatred of God. The second and third questions ask what are the personal and national consequences when the proclamation of the gospel is removed? Brooks does not pull any punches here and is worth a careful meditative study by today’s reader in light current events. Be encouraged by Brooks’ conclusion to this section: “When it is the nearest day, then it is the darkest. There may be an hour of darkness that may be upon the gospel, as to its liberty, purity, and glory; and yet there may be a sunshining day ready to tread on the heels of it” (p. 43).

Part 2

Brook’s second part is his “legacies” or parting thoughts for his congregation when he was no longer at liberty to teach them. I have spent the longest with the tenth:

Labour mightily for a healing spirit. Away with all discriminating names whatever that may hinder the applying of balm to heal your wounds. Labour for a healing spirit. Discord and division become no Christian. For wolves to worry the lambs is no wonder, but for one lamb to worry another, this is unnatural and monstrous. God has made His wrath to smoke against us for the divisions and heart-burnings that have been amongst us. Labour for oneness in love and affection with every one that is one with Christ. Let their forms be what they will, that which wins most upon Christ’s heart should win most upon ours, and that is His own grace and holiness. The question should be, What of the Father, what of the Son, what of the Spirit shines in this or that person? And accordingly let your love and affections run out (p. 46).

Clearly the caricature of Anglican Puritans as divisive is just that, a caricature. Rather they longed for the day when gathered into our heavenly Father’s bosom there will no longer be need of ordinances, of preaching or of prayer. They longed for that everlasting rest in sweet union with their Savior that shaped their days and their actions, as we read here in Thomas Brooks.