Know When to Run

Aug 2, 2016

Ever since I studied the Antinomian-Neonomian controversy that took place among the English Dissenters in London during the final decade of the seventeenth century, I have wanted to write on the debate itself. Part of the impetus for this was that during my studies the Federal Vision controversy was at full steam and it became quite obvious that the two controversies were not only similar in content, but also in style and tone. They resembled each other in matter and method. It seemed to me then and it seems to me now, especially in light of the current Trinity debate, that we can and ought to learn from the English Dissenters on how to, or perhaps more accurately, how not to engage in public theological controversy.

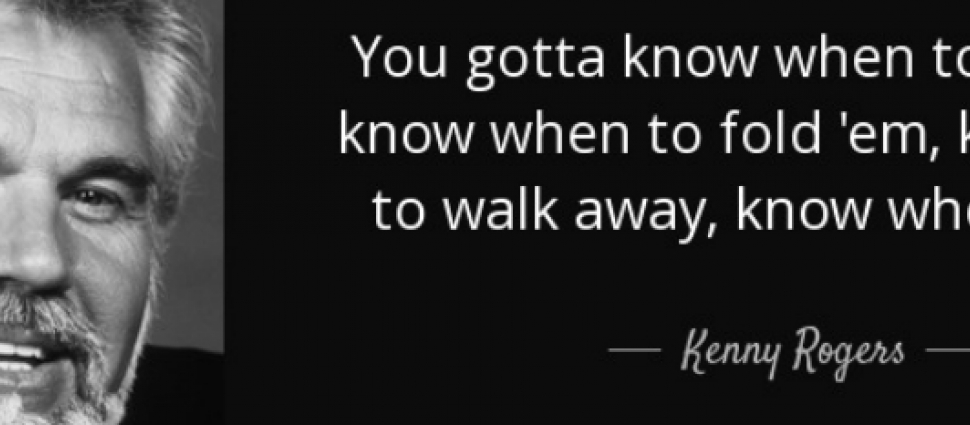

The invitation to contribute to this blog has opened the door and provided the necessary motivation to write a number of articles on the lessons to be learned from this old controversy. I want to begin with a brief history of the controversy, which in itself provides a valuable lesson that may be summed up by the words of a country song, The Gambler: “You’ve got to know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em, know when to walk away, and know when to run.”

A Brief History of the Controversry

In 1690 the Presbyterians and Congregationalists joined forces to help one another financially with a common fund and then ecclesiastically in 1691 by uniting the ministers together on the basis of a doctrinal document. This latter union was well received by many. Matthew Mead took the occasion to preach a sermon on Ezekiel 37:19 entitled, "Two Sticks Made One: Or the Excellency of Unity." Unfortunately, the celebration didn’t last long because a theological controversy that had already been brewing, in part due to the reprinting of the sermons of Tobias Crisp in 1690, would wreak havoc upon the Union.

Besides the lecture hall, the debate played itself out in the public eye via the printing press. Although a number of people wrote on the issues, including Richard Baxter shortly before he died in 1691, it was the book by Daniel Williams (Gospel-Truth Stated and Vindicated) that became the center of debate and the source for the charge of Neonomianism. In this book, Williams attacked the views of Tobias Crisp, but many Congregationalists believed it was aimed at them. They also believed that Williams went too far and expressed unorthodox views himself. In response, Isaac Chauncy published a lengthy reply to Williams in three parts entitled Neonomianism Unmask’d. Williams responded to the first part with his A Defense of Gospel-Truth, only to be answered by Chauncy’s A Rejoynder. Robert Traill also entered the fray when he published anonymously A Vindication of the Protestant Doctrine Concerning Justification, and of its Preachers and Professors from the unjust charge of Antinomianism. This displeased a number of Presbyterians who had recommended Williams’ book and so they prevailed upon Willliam Lorimer to pen a book length response to Traill, An Apology for the Ministers Who Subsribed only unto the Stating of The Truths and Errours in Mr. Williams’ Book.

Many more books and pamphlets kept rolling off the presses, even after all forms of cooperation between the two sides were severed by 1695. People on both sides kept responding and replying to one another so that one gets the impression that all parties were fueled by the need for self-vindication, which could only be accomplished by having the last word.

In reflecting upon the numerous writings of Isaac Chauncy, the Congregationalist historians, David Bogue and James Bennett, remarked: “for what controversialist will be outdone.” A true statement indeed, not only of Chauncy, but also of Williams and the others. And it is equally true of theological controversialists today. The temptation to defend ourselves or to defend our critiques continuously is a clear and present danger. Publishers and editorial policies are helpful in this regard because they compel us to stop. But now with the internet the safeguards are removed in many cases and we are free to post our reviews, responses, defenses, further defenses, rejoinders, surrejoinders and so on.

A Lesson to be Learned

One lesson then that we ought to learn from this past controversy is to know when to fold ’em and when to run away. We need to learn to put to death the desire to have the last word. After all, God’s truth will triumph and its success is not dependent upon our relentless and unending barrage of articles, posts and tweets. This is not to say, of course, that all prolonged public debate is to be dismissed. The English dissenters spent a good deal of time debating the issues in order to maintain their unity and to correct error. Surely, that time was well spent even if it didn’t result in the desired outcome. And yet wisdom dictates that there is a time when the public debate should end and someone has to end it. But what controversialist will be outdone?