Leiden Synopsis and the Divine Attributes (2)

Communicable and Incommunicable Attributes and Divine Affections

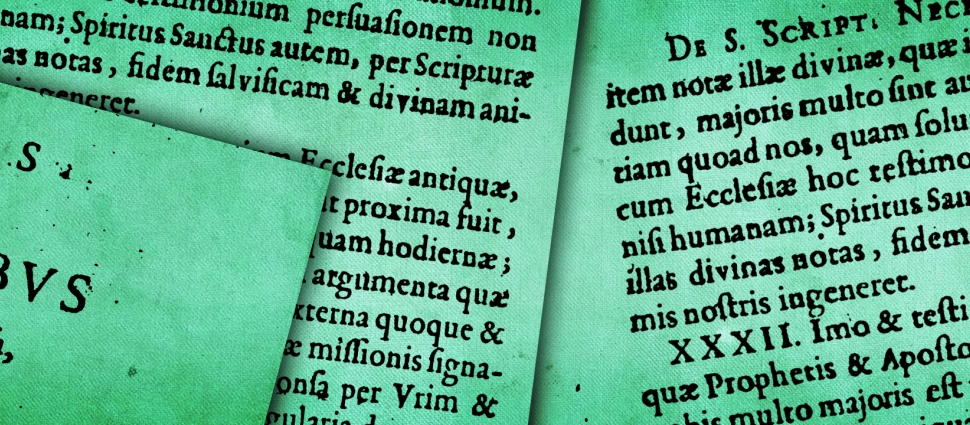

Why does it seem like no two lists of the divine attributes are identical? The previous post showed that part of the reason for this is that God is an incomprehensible and simple being. He is simply always beyond our grasp even though he is within our reach. Yet is there any way of relating his attributes to one another that can help us know God better as he has revealed himself to us in Scripture? Antonius Thysius’ disputation on the divine attributes in the Leiden Synopsishelps us wade through these deep waters a bit by describing logical relationships between some of the divine attributes. While such logical relationships can break down quickly, they can help us develop at least a somewhat less hazy picture of what kind of God we have in view and enable us to remember his attributes better by relating them to one another. After summarizing his division of the divine attributes into incommunicable and communicable ones, this post briefly introduces some questions related to divine affections. I will conclude by using Thysius’ treatment of the divine attributes as a guide to evaluating at a glance the lists of divine attributes in the Westminster Catechisms and Confession of Faith.

While there were different ways of classifying divine attributes, Thysius opted to use the categories of incommunicable and communicable properties. This meant that some terms could be ascribed to God alone while others could be used both of God and of his creatures as reflecting God and as made in his image (165). The incommunicable properties were easier to number than the communicable ones because they included a relatively stable list of what was unique to God with no analogy in his creatures. According to Thysius, simplicity (“on which unity and immutability depend”), infinitude, eternality, and immensity are God’s four incommunicable properties (165). We looked at simplicity in the preceding post. Infinity, which was the second of four incommunicable properties, included eternity and “immeasurability” (immensitas), all of which he called “infallible marks of the Deity.” God’s spiritual essence entailed his simplicity, which is why simplicity qualified the divine attributes as a whole. In this sense, God was also “one,” both in terms of numerical oneness as the only true God and simplicity with respect to not being composed of parts (167). Immutability fell into this discussion because of the implication that the simple God is unchangeably who and what he is (167). Infinitude meant that God was “altogether free from any ending or boundary” (167). Eternality, the third incommunicable quality, meant that he had no beginning, no end, and no succession of time (169). This attribute included his independence. Fourth, and lastly, “immensity is the attribute of the essence of the infinite God, whereby He surpasses all boundaries of essence” (169). Omnipresence is an implication of immensity because if the creation cannot contain God then he also fills it even as he is not bound by it. Note that there is a partial pecking order among the incommunicable properties: simplicity/spirituality is the broadest general description of God; infinitude then encompasses and requires eternity and immensity. These attributes, in turn, imply others, such as independence, omnipresence, etc. While all divine attributes show how God is unique, this set of four attributes was viewed as having no parallels in creation.

Narrowing the list of communicable attributes and relating its terms to each other proved to be a bit more challenging. This is where lists of divine attributes admitted the most diversity among theologians. Communicable attributes are predicated both of God and of creatures by way of analogy (169). We should understand that this meant that we are analogous to God rather than God being analogous to us (181). In other words, we should understand ourselves in relation to God rather than God in relation to us. Reversing this order is one of the primary causes of idolatry, since the pagans remake God in their own images, supposing that God is altogether like them. Thysius sought to organize communicable attributes in a general way. He argued that life, wisdom, will, and power are foremost (169). He noted that even though these are “communicable” attributes, there remains an incommunicable element in them (171). For example, God alone is alive ultimately because he is the source of all life. From life, Thysius branched down into intellect and will, noting that, “This life of God exists in intellect and will” (171). Deducing further from intellect, he added that God’s knowledge, which with wisdom belongs to his intellect, terminates on himself ultimately (173). After distinguishing in passing between God’s efficient and commanding will, Thysius added that the divine will is free and immutable (175). All of these things are immanent in God and they grow out of his incommunicable qualities. As another example, divine power emanates from his potency (175). His potency is absolute in the sense that, “He also could not be capable of more, or less, but He can do all things which He can to do, and He performs his power upon whatever He wills to be, and that without labor or effort” (175). God’s dominion is related closely to this idea. Though this description of logical connections between the divine attributes is not as tight as his treatment of incommunicable attributes, it illustrates that such lists still reflected some attempt at logical arrangement.

Thysius turned next to divine affections, which he distinguished carefully from passions. These divine affections encompassed a good number of communicable attributes. He wrote,

God’s good affections (which in human beings are the passions), and the virtues of his intellect and will (which in mortals are the ethical and moral qualities which designate regulation of the affections), are: truth, love, goodness, gentleness, charity, generosity, mercy, and long-suffering, anger, hatred, justice, and also holiness, etc., and are truly and properly said of God (of course with the removal of every imperfection from them); and they are nothing other than God’s ardent will towards us, and its power and effect in creatures (177).

Two things are noteworthy here. First, this entire list of communicable attributes flows, in some sense, from divine will and from divine power. Life leads logically to intellect (including wisdom and knowledge), which then leads to will and to power, which finally encompasses all other communicable properties (see his examples on pp. 179-183). Second, “passions” in human beings correspond to “good affections in God.” This simultaneously shows a qualitative difference between divine and human “emotions’ and a relationship between them. God does not have passions because he is not moved from anything outside of himself like human beings are. Yet human passions reflect something true about God’s affections. Turretin went so far as to say that human beings would be without passions in heaven, though they certainly would not be without affections. This material not only illustrates how a Reformed author related divine attributes to one another. It should caution people in modern debates over whether or not God is “without passions” against treating terms like “passion,” “affection,” and “emotion” as purely synonymous.

What can we learn from Thysius’ treatment of the divine attributes and can this help us understand the Westminster Catechisms and Confession of Faith better on the doctrine of God? The list of divine attributes in Westminster Confession of Faith 2:1-2 is difficult to navigate. Both paragraphs begin with incommunicable divine properties, though the first includes communicable ones while the second does not. Both paragraphs list what God is absolutely in himself and how he expresses his being in relation to his creatures. The Shorter Catechism sounds more like Thysius’ list, beginning with three incommunicable properties (spirit, infinite, eternal), adding unchangeable before moving fully to communicable properties. “Being” loosely equals Thysius’ placing “life” first among these. “Wisdom,” which would include knowledge, is one half of Thysius’ understanding of “intellect.” “Power” was tied to will in Thysius, while the Shorter Catechism omitted “will” and concluded with “holiness, justice, goodness and truth,” all of which Thysius classified as “good affections.”

In light of this post, the Larger Catechism Q.7 will be a bit more familiar:

God is a Spirit, in and of himself infinite in being, glory, blessedness, and perfection; all-sufficient, eternal, unchangeable, incomprehensible, every where present, almighty, knowing all things, most wise, most holy, most just, most merciful and gracious, long-suffering, and abundant in goodness and truth.

Spirituality/simplicity leads to self-existence (aseity) and infinitude, which brings glory, blessedness, and perfection with it. All-sufficient and unchangeable are relative and absolute attributes, respectively, while the both are incommunicable. They are likely implications of eternality, which would include self-existence in Thysius’ treatment, though that attribute is mentioned separately here. The incommunicable and absolute qualities clearly end with incomprehensible, with a list of communicable attributes rounding out the list.

The Leiden Synopsis helps us better understand the logical relationships between the divine attributes, but it does not solve all of our problems. The Westminster Standards sort of look like an outworking of Thysius’ logical relationships and they sort of do not. Other lists would look sort of similar and sort of different from both of them. This reminds us that every divine attribute implies and informs all of the others, and that beginning with any one of them leads us to marvel at the others. This is what divine simplicity and incomprehensibility mean in practice. We need to learn to make logical connections between God’s attributes. This will help us gain a better and full-orbed view of who God is and well as of what he does, which reflects who he is. Yet studying the divine attributes will always be, and should always be, a humbling affair. It is ultimately only in Christ that we see every facet of the incomprehensible God shine forth gloriously, making him apprehendable to us by faith.

Read the author's previous article here.

Ryan McGraw (@RyanMMcGraw1) is associate professor of Systematic Theology at Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Greenville, South Carolina.