One Covenant of Grace?

Jun 21, 2016

The creeds and confessions of the past continue to serve the Church today because they summarize the eternal truths of Scripture. While the grass withers and the flowers fade, the Word of God stands forever (Isa. 40:8) and therefore faithful summaries of Scripture stand the test of time as well. Yet, for various reasons, particular expressions or teachings of historical creeds and confessions seem strange, easily misunderstood, and may even appear directly contrary to Scripture. One example is the puritan teaching about covenants summarized in the Westminster Confession of Faith. The Confession affirms that upon the fall of mankind God made a redemptive covenant commonly called the covenant of grace (WCF 7.3). There is only one covenant of grace and it is the same throughout the history of redemption, although there are differences in terms of administration (WCF 7.5-6).

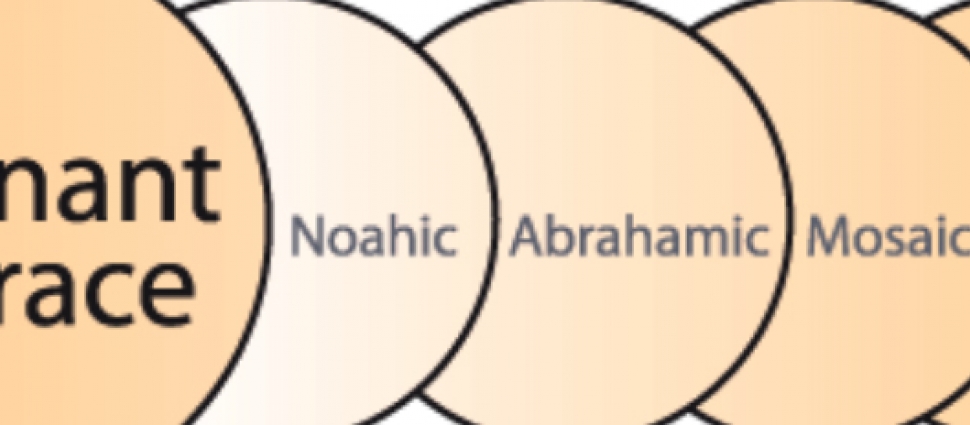

This standard Reformed teaching and manner of expression (the covenant of grace, same in substance, diverse in administration) about the relationship between the Old and New Testaments may appear in the eyes of some to be contrary to Scripture itself. After all, the Scriptures do not refer to a singular covenant of grace but speak of many covenants. For example, the Old Testament records that God made a covenant with Abraham, another covenant with Israel at Mt. Sinai, and still another covenant with David. The author of Hebrews contrasts the old covenant with the new covenant and refers to the new covenant as a second covenant. How then could the puritans teach that there is one covenant of grace? For this very reason, a ministerial candidate in a Reformed denomination once tentatively expressed some semantic concerns with the second sentence of WCF 7.6, which reads as follows: “There are not therefore two covenants of grace, differing in substance, but one and the same, under various dispensations.” He noted that it is imprudent, unnecessary and confusing to speak of one covenant of grace because the Scriptures (Heb. 8:6-9:15) make it unmistakably clear that there are two covenants of grace, the second being better than the first.

A number of preliminary observations are in order before we consider the puritans’ use of the classic Reformed language about redemptive covenants in Scripture:

- First, they didn’t refer to one covenant of grace because they failed to recognize the obvious fact that Scripture mentions more than one covenant. John Ball wrote a book entitled “A Treatise of the Covenant of Grace,” in which there are entire chapters on the numerous biblical covenants, including the Abrahamic, Mosaic and Davidic covenants.

- Second, the term “covenant of grace” is like the term “Trinity,” in that it is not found in the Bible. As Ball says, “we reade not in Scripture, the Covenant of works, or of grace.”

- Third, the puritans were not disparaging, downplaying or denying the differences among the various covenants in Scripture that they grouped together under the one covenant of grace. Both in their personal writings and in the Westminster Standards the puritans elaborated on the differences between the covenants and the discontinuities between the Old and New Testaments.

- Fourth, the covenant of grace should not be seen as another covenant in addition to or distinct from the various biblical redemptive covenants. It is not as if salvation was administered to the Old Testament saints by means of the covenant of grace and not the actual biblical covenant that God had made with them.

The puritans used the classic Reformed covenantal language because it helpfully and concisely set forth their understanding of the biblical relationship between the various covenants and the two testaments. By it they were saying that the various redemptive covenants all share the same substance in that they all consist of the same Christ, the same saving blessings, the same eternal inheritance and the same conditions. In this sense there is only one covenant of grace; but not, to repeat myself, that there is only one gracious covenant in Scripture. God savingly related to his people in the Old Testament in essentially the same way he relates to his people in the New Testament.

The fundamental continuity between the covenants was thus expressed by “the covenant of grace” and “same in substance.” The discontinuity between the covenants was highlighted by the term “administration.” In contrast to the New Testament, Christ and all saving benefits are dispensed or administered in the Old Testament by means of prophecies, types and signs. The Promised Land of Canaan was at times used by the puritans to illustrate the administration of the one covenant of grace in the Old Testament. Since the covenants are the same in substance, the promise of the old and new covenants is the same, namely, heaven. The administration is different. God dispensed the promise by a type or figure—the land of Canaan—in the Old Testament while he dispenses the same promise by the antitype—heaven itself—in the New Testament. Same in substance (same promise) but different in administration (types and antitypes). Or as Westminster divine Stephen Marshall put it: the old and new covenants have the same body but wear different clothes.

Although it may be misunderstood or at first glance seem contrary to Scripture, we who are Reformed should not abandon the covenantal language used by the Westminster Standards. It nicely summarizes and articulates the Reformed understanding, in contradistinction to other views, of the biblical relationship between the various covenants and the two testaments.