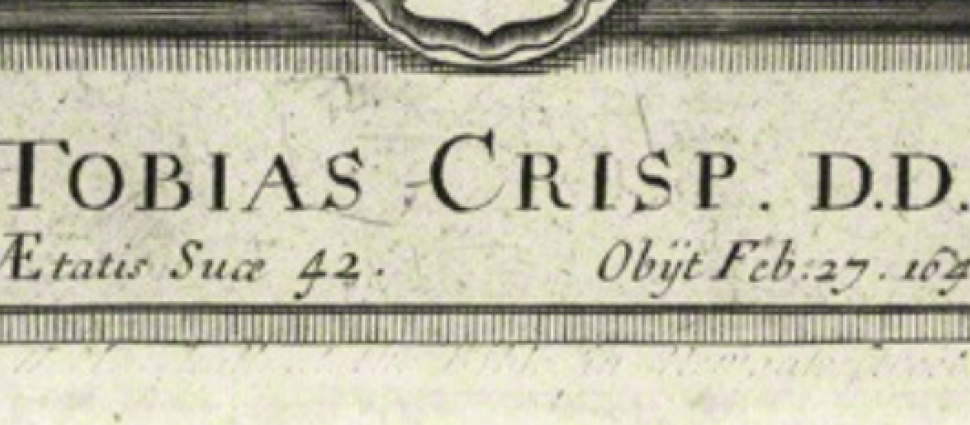

Tobias Crisp (1600–1643): He Was a Bad Guy Right?

Aug 18, 2016

Our presbytery youth camp director this summer assigned Puritan team names for the campers: Watson, Owen, Bunyan, and Perkins. No surprise at an Orthodox Presbyterian Church camp, until the staff and counselors picked a name for their “team.” We chose “Crisp” after the alleged antinomian Tobias Crisp (1600–1643).

Our presbytery youth camp director this summer assigned Puritan team names for the campers: Watson, Owen, Bunyan, and Perkins. No surprise at an Orthodox Presbyterian Church camp, until the staff and counselors picked a name for their “team.” We chose “Crisp” after the alleged antinomian Tobias Crisp (1600–1643). Before you get too upset, please know that we choose an unexpected “anti-hero” name for fun and a teaching moment. So, last year among the Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, and Melanchthon Reformer teams, we selected “Schwärmer” denoting a swarm of bees and the derogatory name Luther applied to the radical reformers. At our campfire one night, two staff members did a skit to introduce the campers to Tobias Crisp. A news correspondent, “Dan Blather,” interviewed Crisp asking about his past and supposed antinomianism. At the end of the campfire, one of our counselors logically asked, “So, he’s a bad guy right?”

Good question. Many would quickly reply, “Yes!” Likewise, when it comes to Crisp, it seems popular to repeat such charges without ever reading him. You know how it goes. The accepted validity of a charge remains directly proportional to how frequently it gets repeated. Others, such as William Twisse, John Gill, and Charles Spurgeon, defended him from antinomianism. This current post attempts to provide a crisper view of Crisp from his own writings.

So, was he a bad-guy antinomian? Strictly, antinomianism affirms that Christians under the new covenant are not obligated to obey the moral law under the old covenant. If this is the case, then Crisp was not an antinomian. For example, in the sermon series published after his death (1643), Christ Alone Exalted, he affirms, “I do not say the law is absolutely abolished, but it is abolished in respect of the curse of it, to every person that is a free-man of Christ.” Against the Arminian and Neonomian influences of his day, he sought to protect salvation by free grace from any hint of man’s contribution. Indeed, Christ alone was to be exalted in man’s salvation from his justification to his sanctification.

So why do people so quickly make the charge? In fact, he is probably the most well-known “antinomian” from seventeenth-century England, with his name usually appearing alongside John Eaton (d.1641) and John Saltmarsh (d.1647). Well, this legalistic turned evangelical preacher was at times misunderstood and maligned for his preaching, which was not in print during his life, and rumors became rampant that he proclaimed a licentious gospel.

Rumors aside, Crisp did indeed set forth teachings that while not strictly antinomian, contributed to such tendencies and prompted such accusations. For example, in order to affirm the absolutely free grace of God in salavation, Crisp taught that “Christ justifies a person before he believes” when such justification is “not known to him.” While we were yet sinners, Christ died for the ungodly justifying them at the cross and uniting them to himself. He later through the work of his Spirit gave them faith, which simply made them aware of their standing in Christ. In this way, redemption accomplished and applied are conflated as the elect become completely passive recipients of their salvation. Faith is not a receiving and resting upon Christ but simply an assurance of prior justification. Some other teachings include: the idea that God’s children cannot offend him, that he never becomes angry with them, and that he never afflicts them for their sin.

Obviously, such positions easily raise concerns for licentiousness as they seem to allow Christians to live wantonly without any fear of God taking action against his beloved children. We can understand how the allegations of antinomianism came, even if Crisp argued that the free-men of Christ have “the power of God in them, which keeps them that they break not out licentiously; the seed of God abides in them, that they cannot sin" (1 John 3:9) in such a manner.

In the end, Crisp places overwhelming emphasis upon God’s act of free grace in justification to the detriment of his work of free grace in sanctification. Likewise, justification as the benefit of Christ becomes foundational in his soteriology rather than union with Christ from which the primary benefits of justification, adoption, sanctification flow. In this way, obedience arises out of justification rather than union with Christ. These emphases hardly help release Crisp from the charge of antinomianism.

Was Crisp a bad-guy antinomian? Not strictly. Still, his doctrine of salvation possessed antinomian leanings and fell outside the bounds Reformed orthodoxy, especially as set forth in the Westminster Standards a in the years following his death.